Efforts to bring advanced typography to the Web have reached an important milestone. Type designers Tal Leming and Erik van Blokland, who had been working to developing the .webfont format, combined forces with Mozilla's Jonathan Kew, who had been working independently on a similar format. The result of the collaboration is called Web Open Font Format (WOFF), and it has the backing of a wide array of type designers and type foundries. Mozilla will also include support for it in Firefox 3.6.

WOFF combines the work of Leming and Blokland had done on embedding a variety of useful font metadata with the font resource compression that Kew had developed. The end result is a format that includes optimized compression that reduces the download time needed to load font resources while incorporating information about the font's origin and licensing. The format doesn't include any encryption or DRM, so it should be universally accepted by browser vendors—this should also qualify it for adoption by the W3C.

Solving different problems

Jonathan Kew has been involved in font technology for some time, and had been following the discussions of how to best support fonts and @font-face directive in browsers. "I thought I could see a possible way forward through both the technical and the political issues surrounding Web fonts, and so I put forward a proposal," Kew told Ars.

That format was called ZOT, and was based on compressed OpenType. "Kew's proposal described a way to compress the individual tables of a SFNT font in a way that not only made the file smaller, but it also offered possibilities for smarter bandwidth use," explained Leming. "For example, a mobile browser could only download the cmap table from the font, decompress it, look at its contents and decide if the rest of the font should be downloaded. This format was liked quite a bit by some of the browser makers, but it wasn't well known among the type industry," he told Ars.

Meanwhile, Leming and Blokland were working on their own .webfont format, which had started to attract support from those in the type industry. The two found themselves spearheading the work quite by accident. "The type industry is a very loose and diverse group of small companies, departments of bigger companies and a lot of individuals," Blokland told Ars. "Nobody appointed us their official negotiators or representatives—Tal and I just got involved because we found it too important to ignore and wanted to find a solution that was acceptable to all parties, foundries, Web developers, user agent builders. So we started working on a new proposal, listening to many parties, trying to address real issues and use open standards," he said.

Some type companies wanted encryption and the ability to compel browsers to enforce licensing. Browser vendors wanted open standards, compression to speed downloads, and didn't want to be responsible for font licensing enforcement. Web developers wanted something easy and straightforward to use.

The proposed .webfont format attempted to address those issues and presented a compromise that would work for everyone involved. It used font data in the same format as OpenType (it was capable of handling future formats, too) so it wouldn't require any new font handling code. It included a rich metadata section, with fields for copyright and licensing information, as well as a private data area that type foundries could use for whatever else they wanted to include. There was basic ZIP-based compression, but no DRM or encryption. A font in the .webfont format couldn't be trivially installed on a computer for use, so it offered some protection from casual copying.

H?kon Wium Lie, the "father" of CSS and a developer at Opera, suggested that Leming and Blokland combine forces with Kew to develop a sort of ?ber-webfont. "Erik and I both liked ZOT, so we were open to the idea," Leming told Ars. "After that, we worked with Jonathan to combine the proposals. WOFF combines Jonathan's ZOT compression and structure with the metadata and private data spaces that we had in our .webfont proposal. We think that we were able to combine the best of both proposals," he observed.

Widespread support

Kew, Leming, and Blokland have published a specification for WOFF, and Mozilla is already hard at work implementing support for it in Firefox 3.6. Firefox will have a default same-origin restriction, so it will only load WOFF fonts from the same domain as the webpage being loaded—a restriction that puts type vendors at ease. The ability to load fonts from other domains can be enabled by a server using Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS).

It seems likely that WOFF could eventually be adopted by browser vendors outside of Mozilla, including Safari—and by extension, WebKit-based browsers like Chrome—as well as Opera.

WOFF has gained wide support from type vendors, as we found when speaking to both larger companies like FontShop International and small, one-man operations like Mark Simonson Studio. "Basically, I like it because it's designed specifically for Web browsers," Mark Simonson told Ars. "It's compressed, so it minimizes bandwidth use and, because it only works in Web browsers, not on the desktop, it's easy to make it clear to customers what it's for when they buy a license."

"FontShop International—home of the world's largest collection of original, contemporary typefaces, the FontFont Library—supports WOFF, since users, designers, and foundries all need a Web fonts format," agreed Ivo Gabrowitsch, marketing director for FSI. "We want to support honest users, offering them the typographic variety they want to have, but are not willing to offer our library to use with insecure technologies, such as 'raw fonts' via @font-face. We want a more protected way of serving professional fonts to the Web, though such a format must respect the issues of all the involved, without the hassle of DRM. The technology must be easy of use with minimal impediments on both Web designers and readers," he told Ars.

Another well-known studio, House Industries, is also excited to take advantage of the new format. "We think that WOFF will ultimately provide a better global typographical solution because it will be more likely to gain the consensus of the browser developers, Web developers, and type designers," House Industries co-founder Rich Roat told Ars. "And selfishly, it will dramatically broaden the market for our typography and make it easier for us to deliver if there is eventually a standard format that is universally accepted."

Dozens of type designers and vendors have already pledged support for the format, and preliminary tools are already available to create WOFF fonts from existing OpenType fonts. "We worked together with the type community to make this happen, have created new business opportunities for type creators, have given new capabilities to Web developers and have given the opportunity for a much more expressive Web for users," Kew said. "It's a win for everyone involved."

It seems that more expressive typography will be working its way to the Web soon. But Kew isn't stopping at basic font support via WOFF. He has also been experimenting with implementing support for advanced typographic features like ligatures, discretionary forms, alternate forms, tabular figures for easier to read tables, and more, all via CSS properties. This advanced support is still in the very early stages of development, but type and design nerds can definitely get a sense of the possibilities by checking out a demo video he created (above) showing off work that may turn up as soon as Firefox 3.7.

Ultimately, all this work will enable websites to take on the expressiveness of print, and extend it further with CSS animations. The benefit of supporting @font-face with WOFF fonts (instead of converting type into images or Flash) is that text will remain accessible. With support already coming in the next version of Firefox, WOFF may gain adoption much faster than many had expected. Like Kew said, it's a win for everyone involved.

Further Reading:

- The latest draft of the WOFF File Format specification is online.

- You can now download an official beta of Firefox 3.6, with support for WOFF fonts, from Mozilla's developer site.

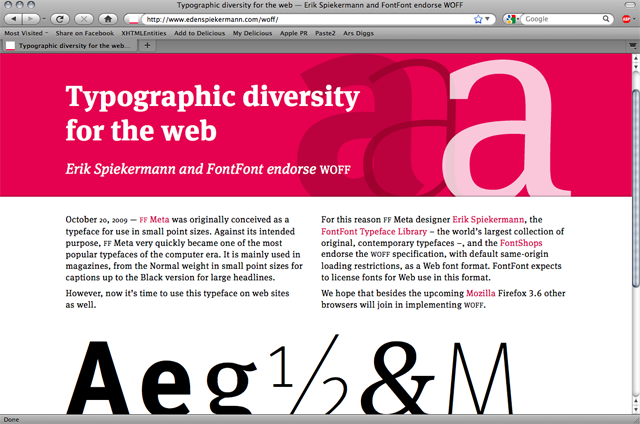

- Typographer Erik Spiekermann has put together a sample page that uses a WOFF version of the popular typeface FF Meta. You'll need the aforementioned beta of FF3.6 to view the custom fonts.

- Mozilla's John Dagget and Jonathan Kew have a post with several examples of more advanced typography generated using CSS properties at Mozilla Hacks.

- We have an introduction to

@font-faceand related CSS technology for those looking for more background, as well as a look at some of the issues that prompted solutions like TypeKit and ultimately WOFF.

Listing image by Photo CC by Gordana Adamovic-Mladenovic

reader comments

39